Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 26th installment.

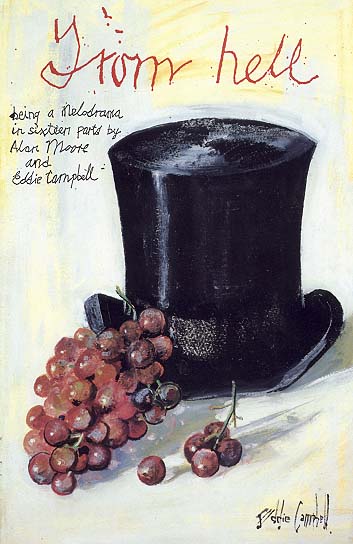

On our ongoing Alan Moore timeline, we’re jumping ahead to 1991 for the beginnings of From Hell, his novelistic, serialized retelling of the conspiracy behind the Jack the Ripper murders of a century earlier. Produced with artistic collaborator Eddie Campbell who had already established himself as a pioneering artist in the field of memoir comics and also dove into iconoclastic mythological retellings for a period—the “From Hell” strip began in the early issues of Steve Bissette’s Taboo anthology.

It bounced from there to small collected editions from Tundra Publishing before continuing on in serialized chunks with Kitchen Sink Press. The massive collected edition of From Hell, which features all the Moore/Campbell chapters plus exhaustive annotations from Moore himself, clocks in at well over 500 pages. Originally published by “Eddie Campbell Comics” and distributed in the U.S. through Top Shelf in 1999, the book has been reprinted under the Top Shelf umbrella ever since.

Even with all the moving around, from publisher to publisher, From Hell feels like a complete, uninterrupted work of graphic narrative. It’s clear on every page that this is not work-for-hire or editorially-directed comic book storytelling. The publisher made no difference at all. This was a work produced at a point in Alan Moore’s career where he could do anything, and this is what happened to interest him. Jack the Ripper was at the core, but the story reaches far beyond the mystery of the Whitechapel murders.

For my reread, I’ll be using the 1999 collected edition, writing about the first half of it this week and the second half next time. I’ll be honest: From Hell is a particularly challenging Moore work to talk about. It’s a tight package, sure of itself and precise. Out of all of Moore’s major texts, this one is probably the least-discussed, likely for that reason. Or maybe because Moore’s annotations thoroughly answer any lingering questions readers may have had, like nails sealing up its own hermetic casing.

From Hell is top-notch Moore, though, and one of his few comic book works that seems unconcerned with any kind of commercial audience. He leans, here, more than almost anywhere else in his comics, toward the art of the story as a pleasure in itself, rather than as a commentary on other stories. The commentary is still here, but it’s subtle. Until Moore points it out.

From Hell, Prologue & Chapters 1-7 (Eddie Campbell Comics, 1999)

Like Watchmen, this is a comic mostly structured as a nine-panel grid, and even though Campbell rarely goes several consecutive pages without expanding one of the panels for emphasis, the underlying architecture remains, and it gives From Hell the steady rhythm of a metronome or a ticking clock.

Campbell’s art, in general, is less traditionally attractive than anyone else Moore had worked with up to this point. There’s a coldness to Campbell’s obsessively scratchy linework, and he’s about as far away from a Dynamic Anatomy/How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way artist as you can get and still be in the realm of comic book art. His characters are forever upright, rigid, and their shifting faces evoke an instability that undermines the stoicism of the whole. It’s impossible to imagine From Hell without Eddie Campbell, which is why the Hughes Brother movie version of this story felt as far afield from its source as the Stanley Kubrick version of Lolita was a distant, alternate reality cousin of Nabokov’s novel.

This is as much Eddie Campbell’s masterpiece as it is Alan Moore’s, it’s just that Moore has more of them to choose from.

Before I get into the story of the graphic novel itself, it’s more than worth noting that From Hell is Moore’s adaptation of Stephen Knight’s Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution from 1976, a book Moore refers to throughout his annotations. It’s far from a page-by-page adaptation of that non-fiction book, as Moore bound other kinds of research into his retelling, but the core of it the central conspiracy around the identity of Jack the Ripper comes from Knight’s work.

Knight’s theory, even at the time Moore was writing From Hell, didn’t have much critical support, and it would be an understatement to say that his “Final Solution” has been discredited by most sources. But that only matters if you’re looking for From Hell to reveal some secret truths about Jack the Ripper, which isn’t what the story is really about. It’s about Jack the Ripper only in the sense that Watchmen is about Rorschach. The truth of the telling is in how it’s told, not in the veracity of the details in the telling. From Hell is as much a fiction as any other Moore comic. It’s historical fiction, heavily-researched, rather than genre fiction, heavily based on nostalgia.

From Hell‘s prologue opens with a bundle of epigraphs: one is a salutation to Ganesa (the Lord of Beginnings, of course, though the god will be referenced in the story later, for other reasons), another is the dictionary definition of “autopsy,” one is a quote from paranormal researcher Charles Fort, and the final one from Sir William Gull.

Gull, real-life Physician-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria, is the foundation of Knight’s Final Solution, which posits the royal physician as the Jack the Ripper killer, and explains a deep conspiracy in which the prostitute murders in Whitechapel were a way to cover-up a royal indiscretion.

Moore doesn’t exactly tell the story as “Gull did it, and here’s why.” But, that’s basically how it ends up unfolding. Perhaps if he had begun the story a decade later, he would have told it precisely that way as a visual essay, like he ends up doing with Promethea but though From Hell is far from a whodunit, it’s also not an essay about what happened 100 years earlier on the streets of London. Instead, it’s a story about social class and consequence. It’s about London itself, and the historical people and places who intersect in this one version of the Ripper legend. It feigns hyper-historical-realism, but that’s largely because that makes the story all the more frightening. It seems plausible, even if it didn’t happen like this at all.

Gull doesn’t even appear until Chapter 2 of From Hell, and even then it’s as a child and then a working physician with no obvious malicious intent. That’s one of the things Moore and Campbell do well in this story show the methodical steps that take Gull from a simple, efficient problem solver to someone who is undeniably evil. But that isn’t even the focus of the first half of this book. No, the first half is about setting the stage, and establishing all of the players.

The Prologue gives us an episode far into the story’s future, with characters we haven’t even “met” yet, though, I suppose, we are meeting them here before we know why they are important. All we learn is that these two old men, Lees and Abberline, who walk along the shore were involved in something particularly nasty some time before. If you read the Prologue unaware that it begins a Jack the Ripper story, you would have no idea what these two characters are going on about, with their references to some vague September and something rotten they once uncovered.

They mostly talk politics, and Lees supposed precognitive powers (which he, depicted here, admits were all a sham). And they end up at Abberline’s place, at what he calls, in reference to the nice pension (and possibly bribes he received, according to Moore’s annotations), “the house that Jack built.”

Most writers would follow up such a prologue with some kind of transition back to these two characters when they were younger, bringing us back through the Ripper story with Lees and Abberline as our narrative tour guides.

Not Moore.

Abberline doesn’t play a prominent role in the story until much later, and Lees appears even later than that.

Instead of doing the obvious, Moore risks reader comprehension (keep in mind, this story was originally serialized in an anthology that came out quarterly in a good year) by giving us a chapter titled “The affections of young Mr. S.”

In this chapter, we meet Annie Crook and her lover, Albert Sickert. Time passes swiftly, from page to page, though without any captions telling us how much time we have to figure that out from the context of each fragmentary scene and we know there are family issues involved with Albert, though we don’t know what. And we know Annie Crook has a baby, and it clearly belongs to Albert. Annie and Albert get married.

The only thing that keeps this from being a pedestrian love story is the speed at which everything unfolds and the constant concern expressed by Walter Sickert, who is obviously hiding something about Albert’s background.

By the end of the chapter, we see Albert, referred to as “Your Highness,” grabbed and taken off by coach, and all Walter can say to Annie is a harsh, “For God’s sake woman! Just take the child and RUN!!!”

The inciting incident. The dominoes tumble down for the rest of the story because of this one relationship. Albert is the Prince of England. The marriage, unsanctioned. The child, a dangerous loose thread.

Chapter Two brings in young William Gull, and as in Chapter One, we get a compressed timeline until the history of Dr. Gull catches up to the narrative present. Hauntingly, William as a child speaks to his father of having “a task most difficult, most necessary and severe” before going on to say, “I should not care if none save I did hear of my achievement.”

Throughout From Hell, Moore includes echoes where the past, present, and future collide, as if the timeline of the story is jumbled from its multiple sources, or as if the story of Jack the Ripper has become unstuck in time, and it can’t withstand a linear telling.

Gull, when grown, is introduced to us through his hands. Campbell gives us panel after panel from Gull’s point of view, as a young man first, then as an adult. As a child we see his hands reach out to dissect a mouse he finds. As an adult we see him sewing up, presumably, a corpse. He is dehumanized and established as interested in, and skilled in, the art of cutting open dead bodies. Creepy enough outside of a Ripper story. Within it, his actions become like the pendulum over Edgar Allan Poe’s pit. We wait for it to swing down at us.

In the second chapter, Moore also introduces the Masonic rituals that play a significant part in the conspiracy Gull’s status as a Freemason lead to his assignment to the royal, um, problem and to the architecture of London, specifically that of Nicholas Hawksmoor, who brought a symbolically pagan design sense to Christian structures.

I could enumerate the small details and textual layers of each chapter of From Hell forever, because this is a dense comic, full of allusion and repetition and resonance and meaning, both stated and implied. So I’ll skip ahead and highlight just a few moments in the remaining handful of chapters in the first half of the collected edition.

Gull takes his assignment directly from the Queen in Alan Moore’s retelling seriously, as he does everything, and he “relieves the suffering” of Annie Crook, who has been institutionalized since her raving about “His Highness” Albert and everything “they” took from her. That would have wrapped everything up, if it weren’t for Walter Sickert and the Whitechapel prostitutes who knew more than they should about the Albert and Annie situation and the blackmail attempts that followed.

Dr. Gull’s work must continue.

Notably, Moore spends as much time exploring the lives of the underclass in these chapters not in any substantially fleshed-out way, but enough to emphasize the social class disparity between the future victims of Gull’s knife and the aristocracy he is more accustomed to. Moore and Campbell romanticize none of this, neither the murders themselves nor the lives of the “innocent” prostitutes. They merely show the unfolding of fate, with narrative techniques so restrained as to seem almost impartial.

Amidst it all, Moore and Campbell provide an extended scene where Gull tours London with the cab-driver Netley, and this is where Moore, through Gull’s exposition, tends towards essay. In the sequence, a virtuoso bit of connect-the-dots history and storytelling that helps to amplify the conspiracy surrounding the killings-to-be, Moore maps out the secret, arcane, architectural history of London, revealing a satanic pattern beneath. It is a kind of baptism, for Netley, and for the reader. The bloodletting is about to begin.

The first murder, of Polly Nicholls, one of the blackmailers who knows too much about Albert, is inelegant and overdone (by Gull and Netley, not by Moore and Campbell, who maintain their measured precision all the way through). In the darkness of night, the constable who stumbles across the dead body of the victim doesn’t even realize that she’s been gutted. That’s discovered later, by the coroner. It’s a sloppy bit of murder and police work all around.

Soon enough, Inspector Abberline comes to investigate, reluctantly, and the Abberline vs. Gull dynamic is established, though Moore doesn’t present it simply as the direct contest that it would become in the hands of a lesser writer (or, if I remember correctly, as it became in the movie version). Moore provides the conflict indirectly. Abberline is more annoyed at having to return to his loathed Whitechapel, but he will do his best to figure out what’s going on. Gull, meanwhile, moves on to his next victim, surgically, as is his approach to everything.

Moore layers in another conflict as well, the enthusiasm of the press, and the newspapermen who, in Moore’s retelling, write the first Jack the Ripper letter (and thereby give the shadowy culprit an identity they can exploit), and then send it to the newspapers. As Moore states in his annotations, “In the case of the fraudulent and press-generated ‘Ripper’ letters, we see a clear prototype of the current British tabloid press in action,” before taking a dig at Rupert Murdoch and the “arcane solar symbol” of The Sun.

And that’s where Chapter Seven reaches its end, with the “Dear Boss” letter that gave the Whitechapel killer a name that has stuck for all time since.

Rereading this comic is like watching someone continually sharpen a bloody knife, and while you don’t want to look away, you also can’t keep staring at it without taking a break.

Let’s take a week off, and return for Chapters 8-14, plus, the Epilogue!

NEXT TIME: More killings. More conspiracy. From Hell concludes!

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.

One extremely Moore-ish device that you didn’t mention, but that’s demonstrated in some of the dialogue you quoted: almost all (or all?) of William Gull’s lines are in iambic meter. Moore did the same thing with V in V for Vendetta. It’s immediately apparent if you read it out loud; on the page, it just provides a general feeling that there’s something a little unusual about this person’s word choices and sentence structure. Both Gull and V are highly intelligent, almost otherworldly creatures who attach great importance to language.

Been meaning to read this but have been badly slacking…soon as I’m done with Swamp Thing I’m all over this one here.

Tim did you know that Grant Morrison is partially responsible for the detailed footnotes at the end of From Hell? According to Steve Bissette here Morrison made some comments back in the 90s about how Moore had “stolen” his basic thesis from Stephen Knight’s book. This made Moore furious (he’d read basically every book about Jack the Ripper out there, and admitted such publicly), but it arguably prompted him to make From Hell an overall better reading experience. I love Moore’s nonfiction writing and his annotations are a breeze to read. They add a lot.

Interestingly this wasn’t the only early 90s comic book by a well-known British Invasion writer to posit that Gull was the Ripper. Garth Ennis and Will Simpson’s “Royal Blood” story arc from Hellblazer (#52-55) was about “a very prominent member of the Royal family” (never directly named) who goes on a murder spree after a demon possession gone wrong–the demon (charming fella named Calibraxis) turns out to be the same demon who went around as Jack the Ripper a century earlier. In issue #54 John Constantine tells a compressed version of the Gull story. It’s very similar to Knight’s book and From Hell (he was a freemason, buddies with Queen Victoria, the women he killed were part of a blackmail plot involving Prince Albert’s daughter, etc.). I have no idea if Ennis and Moore happened upon the same research, or if Ennis was paying homage to the first few installments of From Hell, or maybe it’s just a popular theory among conspiracy-minded comic book writers across the pond.

The cab tour with Netley, which you described as a “virtuoso bit of connect-the-dots history” is one of my favorite Moments of Moore. Just incredibly detailed and intricate, mind-blowing stuff. I wish you had spent more time dissecting it but it’s so virtuosic one might as well just read it again in its entirety.

Q-B: Knight’s book isn’t obscure– it was a bestseller that stayed in print a long time and was the basis for several movies– so it’s not implausible that Ennis got into it on his own.

But if Knight hadn’t existed, Moore would’ve had to invent him. He was a friend of Colin Wilson, an autodidact and a religious wanderer, who became massively successful due to happening upon a style of conspiracy theory that people liked, and then died young. He slightly resembles the pseudo-psychic Lees (at least as Moore portrays him) in two ways: he was subject to seizures and, according to Wilson, he hadn’t meant for his book to be taken so seriously but was too embarrassed to admit it after he became famous.

(Speaking of Lees: Tim, another very Mooreish touch is that even though Lees admits he’s a fraud, the visions he pretends to have are always true. One is near the end, when he points the finger at Gull just because he doesn’t like him; the other is in the prologue, when he demonstrates his shtick to Abberline and improvises the line “See death– five years,” which is when Abberline really will die. It’s a funny idea but also one that Moore treats pretty seriously; Moore is after all someone who based his own personal religious practice on a Roman cult that he admits was almost certainly a hoax.)

Moore’s finest work and Eddie Campbell’s drawings fit the sordid and terribly sad story very well. This is a cold book filled with dysfunctional relationships between men and women, culminating in Gull’s ritualistic slaughters in order to save his gender from a matriarchy, amongst other things.

The footnotes make it for me, anchoring the at times highly eccentric story in meticulously researched history and cheerfully admitted fiction driven partly by Moore’s open heavy distaste for freemasonry.

I’m new to this book. Should I read the annotations at the end? Or should I read the appropriate one after each chapter?